I am a pretty big Robert E. Howard fan and have often been of two minds when reading published versions of his work. The first sympathizes with the "purist" movement who desire to read Howard's stories as Howard wrote them and not the "edited" versions most modern readers are familiar with. The second appreciates the work of Carter and DeCamp did to keep Howard's writing alive as a part of popular culture.

I try to balance these two conflicting mindsets, but as time passes it becomes both easier and more difficult as publishers have begun in recent years to publish anthologies collecting the works as they were initially published. They have finally made it affordable for me to share the experience the purists laud so greatly. But Ace books has recently begun publishing the Age of Conan series, which has really excited my second mindset. Ghost of the Wall the first of the third Age of Conan trilogies was released recently and I am looking forward to reading it. If it is anything like the other two trilogies, it should be a fun ride and that is where the conflict becomes more difficult.

The purists are upset with what was an almost hidden betrayal. For readers like me, who only know better because of the purists, we never would have known that Howard's work had been rearranged, re-edited, and had pastiches fill chronological gaps. Sure, we would have noticed that some of the stories lacked the darkness or sophistication of Howard's best work, but we notice that even in his actual work. It is upon reading Howard's unaltered words that his vision of Conan becomes clear, and it shares little with the pseudo-erotica some pastiches aspire to be or with the filmic representations.

But the new writers aren't as presumptuous as Carter and De Camp. I recently wrote Matt Forbeck, the editor of the Ace Books line, asking him a few questions about the philosophy behind the current publications. It was the first email I had written him that he had not responded to, well at least not directly. Since the email, Forbeck has written a couple of updates regarding the new series on his blog. One of these provided a link to Jeff Mariotte's blog where Mariotte (the author of the most recent trilogy) has written a very nice entry about his appreciation of Howard which answers nearly all the questions I had.

Howard and his friends, H.P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith, frequently borrowed from one another and in a way had shared worlds. The new Ace series seems to me to be writing in this vein. The authors of the Age of Conan books are writing in the time of Conan, but they are writing about other characters living in the rich environment Howard created. Unlike earlier publications, the new authors seek not to be substitutes for Howard, rather these authors are inspired by the Hyborian age and want to explore its possibilities. For me this is the perfect balance of my two mindsets. Having read Mariotte's essay on Howard, I look even more forward to reading his contribution.

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

A Book for Struggling Screenwriters

Recently, a great deal of my coverage has focused on games and the gaming industry. This may have left those of you who first read this site because of my "Want to Write a Supernatural Spec?" post wondering what you are doing reading this blog regularly. Others who came following our first movie review "In the Shadow of Kurosawa" might be wondering if Cinerati ever lives up to its name. Our focus here at Cinerati is to discuss Popular Culture, broadly defined, as our individual professional schedules allow us to write as amateur journalists. Sometimes this leads us to focus too keenly on one, or two, aspects of Popular Culture. Recently this focus has been overly dedicated to the discussion of Comic Books and Games.

Today I would like to recommend a book to all aspiring screenwriter's out there. In fact if you are interested in Hollywood and its workings at all, you must own Conversations with My Agent by Rob Long.

One might be wondering what I, a "character" in The Prisoner and Director of a non-profit devoted to civic engagement of youth, might have to offer as far as recommending books for aspiring professionals. There are after all blogs written by screenwriters who have written blockbusters or written by hard working direct to DVD writers, all of whom could better relate to screenwriters what it takes to be a working writer in Hollywood. That's not my goal. My goal is to provide hope to those who find themselves questioning their choices, staring at writer's bloc, or frustrated at the challenge of getting anyone to even look at your ideas. Is this you? Good, then let me continue.

I first heard of Rob Long's book at an LA Press Club event entitled Mass Market, Smart Content ( I reported on my experience here). The book was mentioned by panelist Scott Kaufer, who mentioned how accurate and entertaining the book was. In the spirit of full disclosure, Scott Kaufer is currently my wife's boss. He wasn't at the time of the event, neither my wife or I had met him before the event, but he is at present. Having said that, this recommendation, like most of Mr. Kaufer's recommendations, was a good one.

Conversations with My Agent (published in 1997), as its name implies, is filled with discussions that Rob Long had with his agent following the end of Cheers on which Long was an Executive Producer and Writer. The discussions are well written, ring true, and are often laugh out loud funny. During the process of reading Long's conversations one becomes familiar with many of the frustrations that writers in Hollywood face on a day to day basis. Everything from "development hell" to the desire to write a novel is discussed. Since purchasing the book, I have returned to the book again and again to reread a particular anecdote or example. The humorous examples always bring a smile to my face. Don't take my word for it, here is an exerpt:

The theme of "not having a conversation" is one that is constant through the book. The relationship of writer to agent is shown as very one sided and the running theme is that all decisions an agent makes are based on the agent, not the writer, getting paid. That may seem a cynical position, but I don't think it is. I believe that the lesson of the book, if there is one, is to remind writers that Hollywood is an industry filled with people who are making money. But these people are also risking resources on an often unproven commodity. You may be an extraordinarily talented and funny writer, but until you have turned a profit you will be viewed skeptically, and as Long demonstrates that skepticism is there even if you have turned a profit.

As a fan of television it is always nice to read a television writer write about why shows don't always work. "The main reason that television sitcoms are so bad is that too many educated people are involved in creating them."

I personally think Long's story about when he talked with his agent about writing a book was one of the most amusing conversations, but if you want to read that you have to buy the book. The book didn't sell as well as it ought, but when I had the opportunity to ask Long why this was the case he shared that it was because the book was too short. At 180 pages, the book is just the right length for the person who picked it up on the shelf at Barnes and Noble to finish the book by the time they go from the rear of the purchase line to the cash register. Whatever the reason...rush to your keyboard and order a copy.

While you are at it, you might want to check out his more recent book.

Today I would like to recommend a book to all aspiring screenwriter's out there. In fact if you are interested in Hollywood and its workings at all, you must own Conversations with My Agent by Rob Long.

One might be wondering what I, a "character" in The Prisoner and Director of a non-profit devoted to civic engagement of youth, might have to offer as far as recommending books for aspiring professionals. There are after all blogs written by screenwriters who have written blockbusters or written by hard working direct to DVD writers, all of whom could better relate to screenwriters what it takes to be a working writer in Hollywood. That's not my goal. My goal is to provide hope to those who find themselves questioning their choices, staring at writer's bloc, or frustrated at the challenge of getting anyone to even look at your ideas. Is this you? Good, then let me continue.

I first heard of Rob Long's book at an LA Press Club event entitled Mass Market, Smart Content ( I reported on my experience here). The book was mentioned by panelist Scott Kaufer, who mentioned how accurate and entertaining the book was. In the spirit of full disclosure, Scott Kaufer is currently my wife's boss. He wasn't at the time of the event, neither my wife or I had met him before the event, but he is at present. Having said that, this recommendation, like most of Mr. Kaufer's recommendations, was a good one.

Conversations with My Agent (published in 1997), as its name implies, is filled with discussions that Rob Long had with his agent following the end of Cheers on which Long was an Executive Producer and Writer. The discussions are well written, ring true, and are often laugh out loud funny. During the process of reading Long's conversations one becomes familiar with many of the frustrations that writers in Hollywood face on a day to day basis. Everything from "development hell" to the desire to write a novel is discussed. Since purchasing the book, I have returned to the book again and again to reread a particular anecdote or example. The humorous examples always bring a smile to my face. Don't take my word for it, here is an exerpt:

ME

We're thinking about writing a feature film spec.

MY AGENT

Wonderful. That's a terrific idea. Do you know why?

ME

Why?

MY AGENT

You'll get it out of your system. You'll write one, it won't sell, and it'll be out of your system. And that will be good. Because you'l never never ever get another chance to write one.

ME

What?

MY AGENT

Please. You'll be busy. You'll be producing your television show or pitching another show or working on someone else's television show.

ME

But --

MY AGENT

We are not having a conversation. I am talking.

ME

But --

MY AGENT

It's a bad career move. It's a waste of time.

ME

But --

MY AGENT

Plus I don't handle feature scripts. It would be handled by someone else at the agency and do you know what? There's nobody here as nice as me.

The theme of "not having a conversation" is one that is constant through the book. The relationship of writer to agent is shown as very one sided and the running theme is that all decisions an agent makes are based on the agent, not the writer, getting paid. That may seem a cynical position, but I don't think it is. I believe that the lesson of the book, if there is one, is to remind writers that Hollywood is an industry filled with people who are making money. But these people are also risking resources on an often unproven commodity. You may be an extraordinarily talented and funny writer, but until you have turned a profit you will be viewed skeptically, and as Long demonstrates that skepticism is there even if you have turned a profit.

As a fan of television it is always nice to read a television writer write about why shows don't always work. "The main reason that television sitcoms are so bad is that too many educated people are involved in creating them."

I personally think Long's story about when he talked with his agent about writing a book was one of the most amusing conversations, but if you want to read that you have to buy the book. The book didn't sell as well as it ought, but when I had the opportunity to ask Long why this was the case he shared that it was because the book was too short. At 180 pages, the book is just the right length for the person who picked it up on the shelf at Barnes and Noble to finish the book by the time they go from the rear of the purchase line to the cash register. Whatever the reason...rush to your keyboard and order a copy.

While you are at it, you might want to check out his more recent book.

Tuesday, January 24, 2006

Looking for an Addition to the Gamers Library? Keep Looking.

As the interests of the gamer and the hobbyist overlap, so too do the interests of the gamer and the collector. People who become serious about experiencing the wide variety of board game entertainment currently, and historically, often find themselves searching for particularly useful resources in their pursuits. In my adventures searching for useful books about roleplaying games I have found Heroic Worlds particularly useful. The Complete Guide to Role Playing Games

particularly useful. The Complete Guide to Role Playing Games was the first book of this nature I purchased. While by modern standards The Complete Guide is nowhere near complete (even for the time it was written), I still find it to be an invaluable resource. In fact, it is the cornerstone of the books about roleplaying games section of my home library.

was the first book of this nature I purchased. While by modern standards The Complete Guide is nowhere near complete (even for the time it was written), I still find it to be an invaluable resource. In fact, it is the cornerstone of the books about roleplaying games section of my home library.

Other books in my library include The Fantasy Roleplaying Gamer's Bible , I own both editions, and Dicing With Dragons

, I own both editions, and Dicing With Dragons . I have many more, but these few are among some of the better resources if you want to understand and collect roleplaying games.

. I have many more, but these few are among some of the better resources if you want to understand and collect roleplaying games.

Recently, my attention has expanded to include a desire for books about boardgames and card games. Ever since I read that first, very dry but very informative, page of The Oxford History of Board Games I have been in pursuit of helpful references regarding board games. In particular, I am looking not just for a checklist with beautiful images of hard to find treasures, but a book like the Oxford that contains descriptions of play. I understand that intellectual property rules may prevent the release of detailed rules, but I would like some description to base my interest on. True, there are some games worthy of purchase merely as examples of extraordinary illustration, but I am first and foremost someone who enjoys playing games.

I have been in pursuit of helpful references regarding board games. In particular, I am looking not just for a checklist with beautiful images of hard to find treasures, but a book like the Oxford that contains descriptions of play. I understand that intellectual property rules may prevent the release of detailed rules, but I would like some description to base my interest on. True, there are some games worthy of purchase merely as examples of extraordinary illustration, but I am first and foremost someone who enjoys playing games.

This is the kind of resource I was hoping to find when I purchased The Games We Played . Sadly, this book was not what I had hoped it would be.

. Sadly, this book was not what I had hoped it would be.

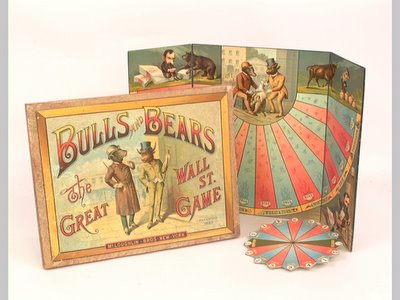

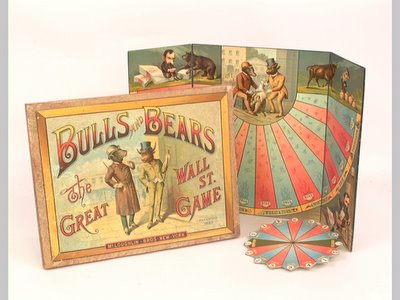

The Games We Played is the companion volume to a museum exhibit at the Henry Luce III Center for the Study of American Culture. As a companion to the exhibit the book is an amazing publication. It contains beautiful photography of interestingly designed board games accompanied by brief comments about what games have to say about the society in which they were created. To be fair though, the analysis is nowhere near the level of The Oxford History. The book provides just enough information about any particular game to give it a social contexts of the design and illustration, but rarely are any descriptions of the game play given. For example Bull and Bears: The Great Wall St. Game (1883) (Parker Brothers would make a similarly titled game in 1936) is described in the following way:

The above quote is useful in a discussion of board game as social artifact, but it does little to discuss the playability of the game. Ideally, a book like The Games We Played would do both. Instead, the reader must settle merely for an interesting discussion of historical relevence. Like most museum exhibits the discussions of the particular artifacts are brief, but not "written down" for a younger audience. Vicissitudes anyone? Why not just say realities or accurate representation? The information provided in the book inspires one to find out more about the people who played the beautifully illustrated games featured between its covers. Sadly, the book doesn't inspire the reader to become one of the people who has played the game. There are great advantages to recognizing the craftsmanship behind consumer products, the removal of utility from them is not one of those advantages. The gamer asks, "if no one is going to play the game, how is this different from a painting?" Then the gamer walks on unfulfilled.

If you are looking for an introduction into board games as a part of American social history, this book is for you. If you are looking for a checklist of some of the games that existed in the nineteenth-century and don't need to know what a game will play like before you buy it, this book is for you. If you want to see the complexity of the art of illustration, this book is for you. But if you are looking for an examination of gameplay as social phenomenon, this book is not for you. The authors have forgotten, it seems, that a part of the social significance of these boardgames is not merely what they represent, but how they represent them. The mechanics used to determine success or failure in Bulls and Bears are just as much a social commentary as are the (probable) Nast illustrations. How random is it? How predictable? I don't know, but I'd like to.

Other books in my library include The Fantasy Roleplaying Gamer's Bible

Recently, my attention has expanded to include a desire for books about boardgames and card games. Ever since I read that first, very dry but very informative, page of The Oxford History of Board Games

This is the kind of resource I was hoping to find when I purchased The Games We Played

The Games We Played is the companion volume to a museum exhibit at the Henry Luce III Center for the Study of American Culture. As a companion to the exhibit the book is an amazing publication. It contains beautiful photography of interestingly designed board games accompanied by brief comments about what games have to say about the society in which they were created. To be fair though, the analysis is nowhere near the level of The Oxford History. The book provides just enough information about any particular game to give it a social contexts of the design and illustration, but rarely are any descriptions of the game play given. For example Bull and Bears: The Great Wall St. Game (1883) (Parker Brothers would make a similarly titled game in 1936) is described in the following way:

By the 1880s, wealth had emerged as the defining characteristic of success in American games, as in life. Bulls and Bears was based on the vicissitudes of the stock market -- an ideal theme for games -- and was designed to make players feel like speculators, bankers, and brokers, if only for a time. Possibly illustrated by famed political cartoonist Thomas Nast, who provided illustrations for some of McLoughlin Brothers' books, the gameboard depicts a nattily dressed bull and bear shearing sheep (under the removable spinner), a sublte commentary on the making of financial empires at the public's expense.

Bulls and Bears is unusual among nineteenth-century board games in incorporating caricatures of contemporary figures. In the lower corners of the board, rairoad magnates William Henry Vanderbilt and Jay Gould, whose speculation contributed to the fanancial panic that inspired this game, smugly read tickert tape showing the value of their stock. Gould is also shown at the top left looking glum as he contemplates the bear market. Cyrus Field, a railroad investor in collaboration with Gould, appears opposite him armed to defend his money bags.

The above quote is useful in a discussion of board game as social artifact, but it does little to discuss the playability of the game. Ideally, a book like The Games We Played would do both. Instead, the reader must settle merely for an interesting discussion of historical relevence. Like most museum exhibits the discussions of the particular artifacts are brief, but not "written down" for a younger audience. Vicissitudes anyone? Why not just say realities or accurate representation? The information provided in the book inspires one to find out more about the people who played the beautifully illustrated games featured between its covers. Sadly, the book doesn't inspire the reader to become one of the people who has played the game. There are great advantages to recognizing the craftsmanship behind consumer products, the removal of utility from them is not one of those advantages. The gamer asks, "if no one is going to play the game, how is this different from a painting?" Then the gamer walks on unfulfilled.

If you are looking for an introduction into board games as a part of American social history, this book is for you. If you are looking for a checklist of some of the games that existed in the nineteenth-century and don't need to know what a game will play like before you buy it, this book is for you. If you want to see the complexity of the art of illustration, this book is for you. But if you are looking for an examination of gameplay as social phenomenon, this book is not for you. The authors have forgotten, it seems, that a part of the social significance of these boardgames is not merely what they represent, but how they represent them. The mechanics used to determine success or failure in Bulls and Bears are just as much a social commentary as are the (probable) Nast illustrations. How random is it? How predictable? I don't know, but I'd like to.

Monday, January 23, 2006

Epaminondas, Hard to Pronounce but Innovative

In gaming circles there is a phenomenon called "Hobbying" that gets a great deal of use, but which the name does little to clue the outsider as to what exactly is being described. To be brief, in the gaming word a "hobbyist" is someone who likes to build, paint, and construct things. Games Workshop has made themselves into a large company indeed by combining strategy wargame behaviors with hobbyist tendencies. They do this by providing a fun rules sets for which you can buy unpainted miniatures and build terrain to host epic battles for your little armies (or as my wife would call them...little men). The game playing aspect of Warhammer is easy to define, it is the playing of the game against other players. They "hobbying" aspect comes in the assembly and painting of figures and the building of terrain. You can tell a true hobbyist when you see someone walk into an arts and crafts store with his significant other who says, "Oh my god...these foam eggs would make awesome Minarets! I can't wait to go home and get to work on these! Oh, oh, are those fake weeds?!"

Inside many a gamer is the person who likes to build things. The game player often desires to be the toy maker, and yet we as individuals often lack the talent to manufacture beautiful miniatures and terrain ourselves. But every now and then comes the opportunity for even the most artistically inept to build an exact wargame, and sometimes it is made necessary because purchasable sets to play are hard, if not impossible, to come by. Imagine if you will that the rules for Chess were readily available, but no one manufactured Chess sets. What would the committed gamer do? If he or she were a hobbyist the answer would be simple, build a set. The sculpture on the pieces may not be pretty, but it would be functional.

I mention this because I recently came upon discussion of a game entitled Epaminondas in the Oxford History of Board Games. The game has a confusing title one can imagine that the fanbase who find this a convenient name is limited to Victor Davis Hanson.

The game is named after Epaminondas of Thebes, who the game rules claim invented phalanx combat. According to Donald Kagan, Professor of Classics at Yale, that honor belongs to Pagondas who used the formation at the battle of Delium (424 BC):

Victor Davis Hanson discusses Epaminondas’ innovations to the phalanx in The Soul of Battle (1999):

While Epaminondas is a difficult name to remember, at least with regard to spelling, the title aptly hints at the goals of the game. Epaminondas is what The Oxford History of Board Games describes as a Space/Attainment game. What this means is that the game is one in which the players "enter or move pieces upon a two-dimensional board with the aim of getting them into a specified pattern, configuration, or spacial position." In particular, the specific goal is to get one of one's pieces across the board into a corresponding position on the opponents end of the board. Essentially, the goal of the game is to move your pieces in such a way as one or more of your pieces ends up on your opponents end. If your opponent can neither eliminate this piece, or move an equal number of pieces onto your end of the board. The manner in which pieces are eliminated is where the name and theme of the game connect. You eliminate opposing pieces by moving larger phalanx's into your opponents existing phalanx. Like Epaminondas defeated the Spartans with his deeper phalanx, so to do you defeat your opponent's pieces.

As I mentioned, sets of this game are nigh impossible to come by, but if you are willing to do a little construction (and I mean very little), you can download the rules here and you can download a copy of a 14x12 grid here (right click and save to retrieve the file). The 14x12 grid is an unusual size, but one that can either be printed and glued to cardstock or constructed using some kind of router to carve a board for use. In addition, all that is necessary are two sets of different colored stones. Though I think I would someday like to see a copy of this game with beautifully carved hoplites facing off on a grid with topographic illustrations.

I haven't played many sessions of the game yet, but the premise is intriguing and may just be too complex for me to actually understand. Like with my first attempts to play Go, I might need someone to describe and demonstrate how to play the game as the written rules leave me needing to play it five or six times more before I actually think I understand the game.

Inside many a gamer is the person who likes to build things. The game player often desires to be the toy maker, and yet we as individuals often lack the talent to manufacture beautiful miniatures and terrain ourselves. But every now and then comes the opportunity for even the most artistically inept to build an exact wargame, and sometimes it is made necessary because purchasable sets to play are hard, if not impossible, to come by. Imagine if you will that the rules for Chess were readily available, but no one manufactured Chess sets. What would the committed gamer do? If he or she were a hobbyist the answer would be simple, build a set. The sculpture on the pieces may not be pretty, but it would be functional.

I mention this because I recently came upon discussion of a game entitled Epaminondas in the Oxford History of Board Games. The game has a confusing title one can imagine that the fanbase who find this a convenient name is limited to Victor Davis Hanson.

The game is named after Epaminondas of Thebes, who the game rules claim invented phalanx combat. According to Donald Kagan, Professor of Classics at Yale, that honor belongs to Pagondas who used the formation at the battle of Delium (424 BC):

On the right of the hoplite phalanx he massed the Theban contingent to the extraordinary depth of twenty-five, compared to the usual eight, while the hoplites from the other cities lined up as they liked, probably in the standard fashion. This is the first recorded use of the very deep wing in a hoplite phalanx, a tactic that would be used with devastating effect by Epaminondas of Thebes and Philip and Alexander of Macedon in the following century” (The Peloponnesian War 2003, 168).

Victor Davis Hanson discusses Epaminondas’ innovations to the phalanx in The Soul of Battle (1999):

From the battle of Delium (424) onward, the Thebans had always massed more deeply than the hoplite standard of eight shields…Epaminondas added a couple of vital ancillary tactical touches. The Theban mass and fighting elite would be placed on the left, not the right, of the Boeotian battle line, in order to smash the opposite elite royal right of the Spartan phalanx…In addition, specialized contingents…and the use of integrated cavalry tactics ensure that the Boeotians themselves could protect their new ponderous and unwieldy columns from enemy light-armed skirmishers and peltasts.

While Epaminondas is a difficult name to remember, at least with regard to spelling, the title aptly hints at the goals of the game. Epaminondas is what The Oxford History of Board Games describes as a Space/Attainment game. What this means is that the game is one in which the players "enter or move pieces upon a two-dimensional board with the aim of getting them into a specified pattern, configuration, or spacial position." In particular, the specific goal is to get one of one's pieces across the board into a corresponding position on the opponents end of the board. Essentially, the goal of the game is to move your pieces in such a way as one or more of your pieces ends up on your opponents end. If your opponent can neither eliminate this piece, or move an equal number of pieces onto your end of the board. The manner in which pieces are eliminated is where the name and theme of the game connect. You eliminate opposing pieces by moving larger phalanx's into your opponents existing phalanx. Like Epaminondas defeated the Spartans with his deeper phalanx, so to do you defeat your opponent's pieces.

As I mentioned, sets of this game are nigh impossible to come by, but if you are willing to do a little construction (and I mean very little), you can download the rules here and you can download a copy of a 14x12 grid here (right click and save to retrieve the file). The 14x12 grid is an unusual size, but one that can either be printed and glued to cardstock or constructed using some kind of router to carve a board for use. In addition, all that is necessary are two sets of different colored stones. Though I think I would someday like to see a copy of this game with beautifully carved hoplites facing off on a grid with topographic illustrations.

I haven't played many sessions of the game yet, but the premise is intriguing and may just be too complex for me to actually understand. Like with my first attempts to play Go, I might need someone to describe and demonstrate how to play the game as the written rules leave me needing to play it five or six times more before I actually think I understand the game.

Friday, January 20, 2006

Stephen King, Joe Bob Briggs, Peter Pan, and Matt Forbeck

Yesterday, I shared a link to Matt Forbeck's, who is a freelance game designer and fantasy author, blog which briefly discussed the copyright issues surrounding Peter Pan. Today Matt has a post that goes into much greater detail on the subject and provides an interesting connection to Stephen King.

One of the most interesting development in the situation, other than the Big Stevo connection, is that even though Disney isn't paying the Ormond Hospital royalties on the Barry prequel, they are contractually bound to give them royalties if they make a movie based on said prequel. That gives a hint at how messed up the copyright situation is with regards to the Pan. Matt has written a wonderful article combining personal narrative with factual presentation, if you are interested in Pan at all please read it. My only criticism is it's reliance on Wikipedia for information. Wiki is an interesting and possibly awsome resource, but as Penny-Arcade has pointed out not one without vulnerabilities. Overt vandalism is rare, but like Comic Book history Wiki is controlled by those with interest in the topic. What type of interest, pro or con, on a controversial topic does affect Wiki entries, though given enough time a kind of "Wisdom of Crowds" or "Cool and deliberative sense" tends to rule the day. Besides, with geek topics, especially non-controversial ones, Wiki has much joss, almost as much as a Kistler profile on Monitor Duty.

But what does this have to do with Stephen King and Joe Bob Briggs? Well the Rock Bottom Remainders are a band that Dave Barry and Stephen King are both members. And Joe Bob Briggs was recently in a fan film based on a Stephen King short story. In fact, thank to the Joe Bob link I discovered Stephen King's Short movies online. The site has a large catalogue of fan adaptations of Stephen King's stories. It even appears, if you are as concerned about IP rights as I am, that Big Steve knows about the site and supports fan productions, but it isn't made expressly clear. To be honest though, I don't think Joe Bob would do anything to hurt Big Steve.

One of the most interesting development in the situation, other than the Big Stevo connection, is that even though Disney isn't paying the Ormond Hospital royalties on the Barry prequel, they are contractually bound to give them royalties if they make a movie based on said prequel. That gives a hint at how messed up the copyright situation is with regards to the Pan. Matt has written a wonderful article combining personal narrative with factual presentation, if you are interested in Pan at all please read it. My only criticism is it's reliance on Wikipedia for information. Wiki is an interesting and possibly awsome resource, but as Penny-Arcade has pointed out not one without vulnerabilities. Overt vandalism is rare, but like Comic Book history Wiki is controlled by those with interest in the topic. What type of interest, pro or con, on a controversial topic does affect Wiki entries, though given enough time a kind of "Wisdom of Crowds" or "Cool and deliberative sense" tends to rule the day. Besides, with geek topics, especially non-controversial ones, Wiki has much joss, almost as much as a Kistler profile on Monitor Duty.

But what does this have to do with Stephen King and Joe Bob Briggs? Well the Rock Bottom Remainders are a band that Dave Barry and Stephen King are both members. And Joe Bob Briggs was recently in a fan film based on a Stephen King short story. In fact, thank to the Joe Bob link I discovered Stephen King's Short movies online. The site has a large catalogue of fan adaptations of Stephen King's stories. It even appears, if you are as concerned about IP rights as I am, that Big Steve knows about the site and supports fan productions, but it isn't made expressly clear. To be honest though, I don't think Joe Bob would do anything to hurt Big Steve.

Thursday, January 19, 2006

First DC Attempts to Get Me to Stop Buying Comics..Now Marvel Joins In

For me there are two truly iconic superhero costumes. These costumes have come to represent more than just the hero wearing them, they have come to represent the company publishing them. From DC comics, that costume is Superman's costume. No matter how many times they play with it, they always have to return to the iconic one. Why? Because the image has become so ingrained in the collective consciousness that the bold S has meaning outside the medium in which it was created. The same is true for Spider-Man. Peter Parker's character revolutionized comic book storytelling and the costume was an innovative imagining. Sure Marvel Comics have tampered with the costume temporarily in the past, and in doing so have created one of Spidey's most popular villains. But the newest costume change, and its association with Marvel's most fickle costume changer Iron Man are just too much. Iron Man changes costumes all the time. Will the same be true of Iron Spidey?

I hope not. Let us hope that Iron Spidey is a precursor to the "Red Arachnid" foe of Spider-Man.

Matt Forbeck Has News on New Peter Pan Prequel

Matt Forbeck discusses a controversy surrounding the 2004 Dave Barry prequel to Peter Pan and the reaction of the Great Ormond Street Hospital.

After reading the article go immediately and watch Finding Neverland and 2003's Peter Pan. Who doesn't love Jason Isaacs as Hook? Hmm...who?! YOU! Why I oughta!

After reading the article go immediately and watch Finding Neverland and 2003's Peter Pan. Who doesn't love Jason Isaacs as Hook? Hmm...who?! YOU! Why I oughta!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)